Save articles for later

Add articles to your saved list and come back to them any time.

The critical question flowing from the latest US Federal Reserve Board rate rise is what happens next.

Will it pause its unprecedented rate-hiking cycle of 10 increases in just over a year? Will there be another increase in June? Will it be cutting rates before the end of the year?

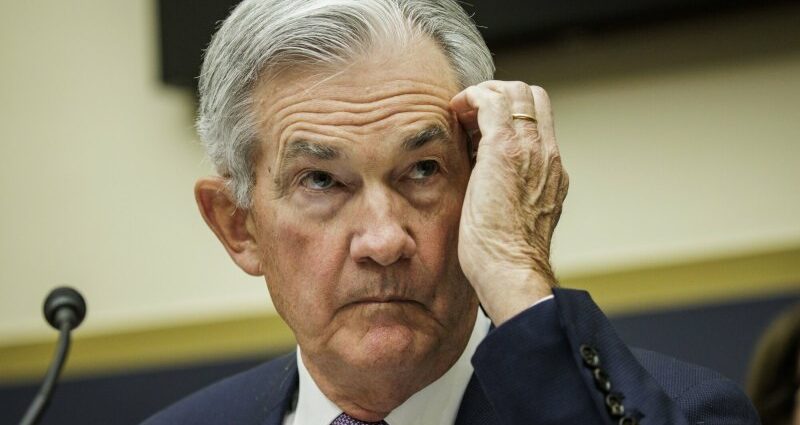

Traders are concerned about key interest decisions to come from US Federal Reserve’s Jerome Powell.Credit: Bloomberg

Fed chair Jerome Powell provided little guidance towards an answer, although he did say the central bank doesn’t expect to cut its federal funds rate – it’s now targeting a range of 5 to 5.25 per cent, the highest since mid-2007 – this year. That’s at odds with the bond market, which is pricing in an unwinding of the rate rises from as early as September.

Powell said it would take some time for the US inflation rate to decline “and in that world, if that forecast is broadly correct, it would not be appropriate to cut rates and we won’t cut rates.”

He said support for the latest rise was “very strong across the board” but also that there was a sense that “we’re getting close [to the peaking of rates] or maybe even there”.

Notably, the language of the official statement from the Fed’s Open Market Committee included an important omission, dropping the line in their March statement that said the committee “anticipates that some additional policy forming may be appropriate”.

Instead, the committee said that, in determining the extent to which more policy firming might be appropriate, it would take into account the cumulative tightening of policy, the lags with which monetary policy affects economic activity and inflation and economic and financial developments.

Powell described that change in language as “a meaningful change”.

There are two wild cards that have emerged in the US that could significantly shift the direction of US monetary policy and bear out the financial market conviction that this rate rise will be the last in this cycle.

The crisis amid America’s regional and local banking sector is continuing. After the collapse of three mid-sized banks – the Silicon Valley, Signature and First Republic banks – another is tottering.

Wall Street fell after Jerome Powell’s press conference following the announcement of the rate rise. Credit: AP

Shares in PacWest, a Beverly Hills-based lender (predominantly for property), tumbled 50 per cent on Wednesday and the bank is scrambling to raise fresh equity or find a buyer. Other mid-sized and smaller banks are also experiencing sharp and destabilising share price declines.

Powell said at his press conference that the turmoil in the banking sector appeared to be creating “even tighter credit conditions for households and businesses”.

While the big US banks have been largely unaffected by the liquidity and solvency problems experienced by the regional and local banks, it is those smaller banks that do most of the heavy lifting in providing credit to households and small and medium-sized businesses and do most of the commercial property lending.

In the midst of a level of banking system stress not experienced since the 2008 financial crisis, the potential for a material credit crunch that would significantly reduce the availability of credit, slow economic activity and undermine the commercial property market is increasing.

A contraction in lending is akin to an increase in interest rates and would occur on top of the contractionary effects of a monetary policy that now sees the federal funds rate above the US inflation rate.

Powell himself said that, in principle, the Fed wouldn’t have to raise rates quite as high as they would have had the problems in the banking sector not happened.

The other event that could radically change the Fed’s policies would be a US default on its debts.

With Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen warning this week that the “X date” – the day when Treasury runs out of the cash to meet its commitments – could arrive as early as June 1, and the Biden White House and Republican-controlled congressional House in a stand-off, the risk of an imminent default has risen.

The Beverly Hills-based lender is the latest US bank heading for collapse. Credit: Bloomberg

Powell said no one should assume that the Fed could protect the economy from the potential short and long-term effects of a failure by the government to pay its bills on time.

“We’d be in unchartered territory and the consequences on the US economy could be highly uncertain and adverse,” he said.

“We shouldn’t even be talking about a world in which the US doesn’t pay its bills,” he said.

A default would be likely to cause chaos in bond, share and currency markets, and not just in the US. However resolved, it would do lasting damage to US financial markets and their status – the bond market in particular – as global safe havens.

With the Republicans demanding cuts to core Biden administration programs as the price of lifting the debt ceiling and Joe Biden insisting on a separation of the debt ceiling issue from any discussion about reducing budget deficits, the odds on a default are now probably as short as they have ever been in the long history of political brinkmanship over the debt limit.

If either the banking system stresses deepen or the unthinkable happens and there is a default by the US government on any of its financial obligations the Fed would have to relegate inflation on its list of priorities to focus on the stability of the US and global financial system. In those circumstances, anyway, inflation would probably cease to be an issue because the US would plunge into recession.

Absent further severe disruption in the banking sector and/or a default, Powell thinks the US economy can avoid a recession although he conceded that the bank’s staff continue to expect a “mild” recession.

They might be right and, even without the wildcards, the recession might be something other than mild.

The history of US monetary policy says that once the peak of a rate cycle is reached – and the latest increase might well be that peak – the first cut is no further than six months away.

Over the past three weeks, two of the key commodities that are regarded as key indicators, even predictors, of global economy activity have fallen sharply.

The copper price is down about 6.5 per cent and the oil price 17 per cent despite the OPEC+ production cuts – 1.2 million barrels a day – that are supposed to be implemented this month.

After rising sharply, to more than $US87 a barrel when those cuts were announced, the price of Brent crude has tumbled to just over $US72 a barrel. The benchmark price for oil produced in the US, the West Texas Intermediate price, has plunged 18.5 per cent and is trading well below $US70 a barrel.

The behaviour of those commodities signals a significant slowdown in global activity within a global economy that was flirting with recession even before the US regional banking crisis developed. (That crisis, ironically, was sparked by the impact of the Fed’s monetary policy on the value of the banks’ holdings of low-yielding government bonds and mortgages).

While the markets might be overly optimistic in anticipating the start of a rate-cutting cycle in September (unless one or both of the wild cards are drawn) they might prove more prescient than the Fed officials in predicting the start of a reversal of the rate cuts before the end of this year.

The history of US monetary policy says that once the peak of a rate cycle is reached – and the latest increase might well be that peak – the first cut is no further than six months away.

The Business Briefing newsletter delivers major stories, exclusive coverage and expert opinion. Sign up to get it every weekday morning.

Most Viewed in Business

From our partners

Source: Read Full Article