Save articles for later

Add articles to your saved list and come back to them any time.

Stan Savige, who at the age of 12 left school at little Korumburra, south Gippsland, to become a blacksmith’s striker, learnt his soldiering the hard way.

Born in Morwell in 1890, the son of a struggling butcher, Savige began his first war as a rifleman on Snipers Ridge at Gallipoli.

Yet he rose to lead troops through two world wars, eventually becoming Lieutenant-General Sir Stanley George Savige, one of Australia’s most decorated soldiers.

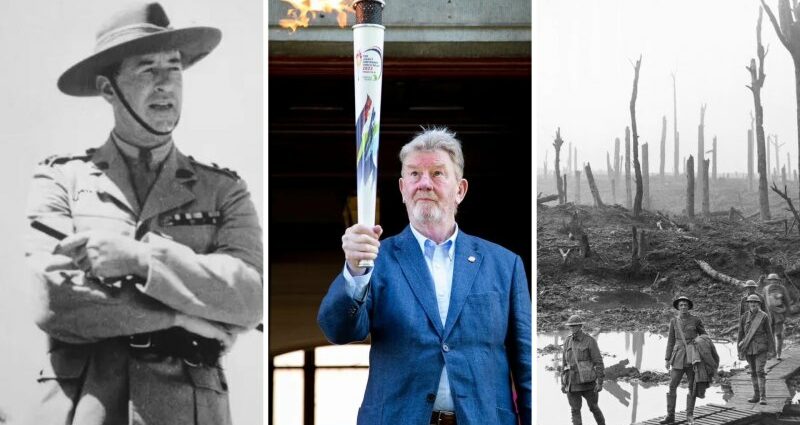

Lieutenant-General Stanley Savige at Lae, New Guinea in 1944.Credit: Australian War Memorial

Along the way, aged 28 in 1918, he is credited with almost single-handedly saving 70,000 Assyrian refugees from slaughter.

Famed for his astonishing courage on the battlefield and later his common touch with soldiers, his most lasting work came in peacetime between the wars.

In 1923, he set up a club for ex-servicemen in Melbourne, having been inspired by a similar club in Hobart, named Remembrance, established by one of his former commanders, Major-General Sir John Gellibrand.

Soon, the club’s purpose expanded as a charitable organisation to ensure war widows and their families were not condemned to the indignity of poverty.

Australian soldiers amid the devastation of Pozieres.Credit: Australian War Memorial

And so, precisely a century ago, was born Legacy, an organisation that spread nationwide and even today assists thousands of families.

Years before establishing Legacy, Savige made his name for bravery in the hell of the Western Front of France and Belgium, and in Iran.

Stanley Savige’s grandson, Stan Waters, holds the Legacy torch.

At Pozieres – where 23,000 men were killed, wounded or taken prisoner in July and August, 1916 – he ran a message through a storm of shellfire. The soldier running beside him was never seen again.

Legacy’s legend, it happens, is that its goal came from the lips of an unnamed dying soldier at Pozieres: “Look after the missus and the kids”.

As Anzac Day 2023 dawns, Legacy’s flame and its message has returned to those old battlefields where Savige, himself the eldest of eight children raised in straitened circumstances, found his life’s purpose.

The Legacy Torch Relay presented by Defence Health, which will wend its way across the world to Australia, raising funds for the families that still rely upon Legacy’s generosity, began in the now peaceful little village of Pozieres, northern France, on Sunday.

On Anzac Day it will travel to the villages of Bullecourt and Villers-Bretonneux, and on Wednesday it will shed its light during the evening sounding of The Last Post at Menin Gate, Ypres, in Belgium.

All were familiar places to the young Stan Savige.

Menin Gate at Ypres, Belgium, is inscribed with the names of more than 54,000 soldiers who perished in WWI.

In the bloody second Battle of Bullecourt, where 7,500 Australians died or were wounded in May, 1917, Savige was mentioned in dispatches and recommended for the Military Cross for “conspicuous gallantry”. Finding himself in a front trench, he held together his fellow troops while under fierce counter-attack.

During the Battle of Passchendaele outside the ruined city of Ypres, Belgium, where 38,000 Australians were wounded or died in October 1917, he was again mentioned in dispatches for conspicuous gallantry. Under heavy fire, he ventured into no-man’s-land repeatedly to lay out “jumping-off” and direction tapes for troops to form up, then guided them into battle, remaining at the front throughout the worst of it.

His most daring exploit came in 1918 in Persia (now Iran), after he had volunteered to be a member of a small military expedition known as Dunsterforce, after its commander, Major General Lionel Charles Dunsterville.

Soldiers carry a wounded mate through the mud during the battle of Passchendaele in Flanders in WWI.Credit: Getty Images

Savige was in charge of a tiny group of sergeants from Australia and other Commonwealth countries who, after Turkish forces had captured the city of Urmia, found some 70,000 frightened Assyrian refugees fleeing from large numbers of attackers mounted on horseback.

The refugees were facing slaughter and young girls among them were being snatched to be sold into sexual slavery.

Savige, with eight sergeants and at one point, an Assyrian and an Armenian up for the fight, formed a rear guard to hold off the attacking Turks and Kurds. Dodging on horseback from position to position, and employing three machine guns spread across a valley, this tiny force fooled the pursuers into believing they were facing much greater numbers.

Assyrian refugees near Urmia, Persia, during WWI.

After seven hours of hard fighting without food or water, exhausted and almost out of ammunition, Savige and his men gained brief relief when a dozen British cavalrymen arrived.

He wrote later “throughout the fight we were forced not only to carry our machine guns but also our supply of ammunition. With rifles slung and a machine gun on the right shoulder with four magazines in the left hand, we guided our horses in the mad gallop from position to position, fired at each time from the front and both flanks, yet, strange as it may appear, we did not sustain a casualty and only three horses were lost”.

Over several days, Savige and his little band shepherded the tens of thousands of Assyrian refugees to relative safety.

“The stand made by Savige and his eight companions … against hundreds of the enemy thirsting like wolves to get at the defenceless throng was as fine as any episode known to the present writer in the history of this war,” wrote Australia’s official war historian, Charles Bean.

Stanley Savige during WWII.Credit: Australian War Memorial

Savige was mentioned in dispatches a third time and awarded a Distinguished Service Order to go with his Military Cross.

He remains a hero to Assyrians. The large Australian Assyrian community still honours his memory every Anzac Day.

His grandson, Stan Waters, of Wandon, near Lilydale, has marched under the Assyrian banner on Anzac days in both Sydney and Melbourne.

“A lot of those people still swear black and blue that they wouldn’t be here if it hadn’t been for my grandfather,” Waters said.

Savige returned to battle in World War II, commanding troops in Greece, North Africa, New Guinea and Bougainville.

He died in 1954 and was buried in Kew Cemetery.

“He was 64,” said his grandson. “I think he was just worn out.”

And yet the flame of Legacy that Stan Savige started a century ago burns on, clear across the world.

The Morning Edition newsletter is our guide to the day’s most important and interesting stories, analysis and insights. Sign up here.

Most Viewed in National

From our partners

Source: Read Full Article

-

Tables restaurant in Denver is closing after 17 years

-

Cliff dramatically collapses onto UK beach that’s now no-go zone during heatwave

-

Exams return for class of ’22 who sat the GAT

-

My Big Fat Indian Wedding! Billionaire's nephew weds painter's son

-

Greta Thunberg says it is 'time to hand over the megaphone'