Fear and dread in the shadow of a second Chernobyl: With Europe’s largest nuclear plant now in Putin’s hands, a brave, brilliant and deeply worrying dispatch from the town staring armageddon in the face

- Europe’s largest power plant in Nikopol, Ukraine, is at the heart of the conflict

- If the power supply is cut off to keep it cool there could be a deadly fallout

- UN inspectors are expected to go to the power plant in Southern Ukraine

From our vantage point, the ‘second Chernobyl’ does not suggest a potential for mass destruction. Nor the reckless and malignant use to which it is currently being put.

Zaporizhzhia nuclear power plant — Europe’s largest atomic facility — is no more than a collection of geometric shapes on the south eastern skyline, about five miles away. The shimmering expanse of the Dnieper river lies between us.

But then comes the faint rumble of out-going Russian artillery from somewhere among or alongside those shapes. Whatever has been launched there is now heading our way, very fast. We have been taught that already, during what has been a long and uncomfortable morning.

‘We cannot stay here,’ warns our guide, local consultant urologist Dr Artem Lebedev, as we scan the horizon from our car.

‘It is very dangerous. People will be worried that [our] presence has been spotted from the far bank and so draw the [Russian] fire to their street.’

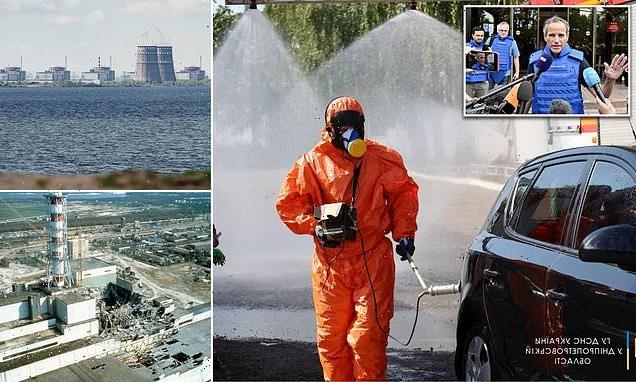

Members of the State Emergency Service attend nuclear disaster response drills amid shelling of Zaporizhzhia Nuclear Power Plant, as Russia’s attack on Ukraine continues, in Dnipro, Ukraine

You have probably never heard of Nikopol. You would not want to be there now. Night and day for the past six weeks, it has been under constant Russian artillery fire. But there is another factor that makes the situation here uniquely alarming.

Nikopol is the closest town on the Ukrainian-held shore of the Dnieper to the giant Zaporizhzhia power station, which was overrun by Russian forces in early March.

Today, the plant, with its six nuclear reactors, is still in Russian ‘control’. That last word is questionable. What is happening — and what might happen — at the facility has become not so much an international cause celebre as a worldwide danger.

Though also built in the Soviet era, the plant is of a far safer design than the one at Chernobyl in northern Ukraine, which blew up in 1986 causing radioactive fallout across Europe.

But, unlike Chernobyl, the Zaporizhzhia plant is on a hotly contested frontline of Russia’s war in Ukraine. It was fought over at close quarters in March. The dangers are obvious.

The functioning reactors need a constant power supply to keep cool. If that power is interrupted or if the plant’s radioactive waste storage facilities were to be hit, there is a risk of deadly fallout.

Ukraine has accused Russia of using the nuclear plant as a military base from which artillery has been fired at Ukrainian-held territory.

There have been reports backed by images that buildings in the plant — including a reactor — have been damaged by missile or shell fire. Civilian employees have become casualties. Both Ukraine and Russia blame the other for this potentially catastrophic targeting.

Earlier this month President Volodymyr Zelensky accused Russia of waging ‘nuclear terror’. UN Secretary General Antonio Guterres said that any attack on Zaporizhzhia was ‘a suicidal thing’.

Energoatom, the Ukrainian company that ran the plant, called for international peacekeepers to protect a demilitarised zone around the plant.

A general view shows the Zaporizhzhia nuclear power plant, situated in the Russian-controlled area of Enerhodar, seen from Nikopol in April 27, 2022

Two of the reactors remained in operation at the start of this week. But one was shut down on Thursday after what Energoatom said was Russian shelling in the immediate vicinity. The Russians blamed the Ukrainians.

On Thursday, inspectors from the United Nations International Atomic Energy Agency finally managed to reach the plant after being delayed by nearby fighting. A number will remain on site over the coming days.

Meanwhile, across the river, Nikopol continues to be shelled and makes provision for a doomsday scenario. What is it like to live in such a place, under such an existential threat?

We were told by the Ukrainian military authorities that Nikopol was a closed zone. But residents and civic leaders told us they wanted the world to know.

And so on the day that UN inspectors went to the nuclear plant, the Mail spent several unsettling hours in the town that lives under the shadow of both conventional war and nuclear disaster.

To reach Nikopol, we leave Mykolaiv as we had arrived — during a Russian missile barrage.

The air-raid sirens wail and there is a thump, thump, thump of impacts across this south-eastern city, from which Ukraine’s counter-offensive towards occupied Kherson was launched earlier this week.

We hear that Nikopol has also been hit overnight — as usual. A dozen homes, shops, a pharmacy, college buildings and a sports hall were damaged or destroyed. Thankfully, there is only one casualty — a 57-year-old woman with injuries.

Because of destroyed road bridges we have to take a more circuitous route. Even so, the war is never far away.

A little way outside Mykolaiv, two Ukrainian attack helicopters skim across the road ahead of our car at tree-top height, heading towards the fighting.

Then, close to Dnipro, we chance upon and overtake a convoy of half a dozen white SUVs bearing the blue UN acronym. These are the atomic inspectors heading for the Zaporizhzhia plant.

The last stretch takes us between mile after mile of moribund sunflowers waiting to be harvested. Finally, we reach the banks of the Dnieper and under a lowering sky full of rain we turn into Nikopol itself. The closest Russian-held shore is only 2.5 miles away.

Chernobyl, Ukraine in 1986, a few weeks after the worst nuclear disaster the world had ever seen

Nikopol is a tough, heavy industrial town in what would otherwise be an idyllic setting. The roads are rutted and most retail businesses have closed. But a large metalworks is still functioning and so, while most of the residents have left, the town is not entirely deserted.

Soon we begin to see evidence of sustained shelling; a police station without a roof, several apartment blocks with chunks torn out of them.

We are being hosted by surgeons at the local hospital. The corridors are echoing and strangely empty. No one wants to be an in-patient here and clinical appointments now finish at midday so that doctors and patients alike can be home and in their cellars before the shelling really gets under way.

‘We are not a military hospital but we are dealing with a lot of military-style injuries,’ says Dr Lebedev who is big and jolly and resembles Alexei Sayle.

‘Generally, we remove the shrapnel, patch them up and then they leave as fast as possible. It’s too dangerous to stay here. The more serious cases we send on to other cities.’

Like the residents, the doctors have learned to adapt.

‘I would like to tell you how people live here, under these conditions,’ says Dr Lebedev. ‘For example, I could not come to meet you earlier because of the shelling. As soon as there was a break, I jumped in my car and came.’

‘All the people who remain here behave in the same way, like hunted animals,’ says Dr Valerii Tumanov. ‘We are always listening, alert before we move.

‘I have a little cellar only a few metres square and that is where my wife and I sleep on a door for a bed every night.’

As he says this, the window in the second-floor office where we are meeting is rattled by the shockwaves from an artillery strike.

‘I think we better move to a room that is not south-facing,’ says Dr Lebedev. ‘It will be safer.’

We move to an office across the corridor. The sounds and vibrations of what becomes a continuous barrage follow us. It does not feel ‘safer’ given the paper-thin walls, but it is the gesture that counts.

Within days of the invasion, the Russians reached Enerhodar, a town constructed to house workers at the next-door nuclear plant.

There was a brief battle in which units of Ukraine’s National Guard were outnumbered and overwhelmed. The power station was occupied and the civilian workers, who continue to manage the plant, effectively held hostage at gunpoint.

The Russians reached the riverbank opposite Nikopol on March 4 and sank the ferry that plied between the two shores with artillery fire. And so Nikopol’s long ordeal began. Fears of a nuclear catastrophe on its doorstep grew.

Iodine tablets, that protect against radiation-induced thyroid cancer, were distributed to residents of the town and surrounding villages in March.

The EU has said it will provide a further 5.5 million tablets to be taken by civilians living further afield.

International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) chief Rafael Grossi spoke to the media in Zaporizhzhia on September 1, 2022, as UN inspectors prepare to head to the Russian-held nuclear power plant in southern Ukraine

The doctors discuss this as the windows once again shake to the rolling thunder of a Grad rocket strike on the edge of town.

‘What we fear is not so much a classic nuclear explosion, with blast and a mushroom cloud, but that the plant will become a “dirty bomb” of massive radioactive fallout,’ says Dr Tumanov. ‘The reactors are only 8 to 9 km (about 5 miles) from where we sit here. A disaster will be very dangerous for the whole region, for Europe.

‘But Nikopol would be ground zero, like (the now abandoned city of) Pripyat after Chernobyl. It will be a catastrophe. And yet the Russian shelling that you hear is coming from Enerhodar and the vicinity of the plant.’

How does he know? ‘We are in direct contact with the people who remain there. They have eyes.

‘We have also spoken to some workers who managed to escape. And they have described the reckless behaviour of the Russian soldiers at the plant.

‘It’s like those Russians who dug trenches in the (highly irradiated) Red Forest at Chernobyl. They have not been informed of the dangers.

‘The employees who are still running the plant have not been able to stop the Russians going into contaminated areas such as store rooms for used protective equipment. They point guns and the civilians have no choice but to let them do it.

‘The stupidity is beyond belief. They say the soldiers there are just imbeciles with weapons.’

Another snapshot of the Chernobyl power plant, three days after the explosion. Now Nikopol lives on a knife edge

Nikopol lives on a knife edge. There is a contingency plan for a mass evacuation in case of fallout from across the river. There are radiation sensors in the town and the mayor gives daily updates of their readings on social media.

Unlike most other Ukrainian cities under attack, Nikipol does not use air raid sirens. The threat is simply too close.

‘Mykolaiv is usually hit by rockets that give them about 30 seconds warning before impact,’ says Dr Lebedev. ‘Here we are under close range artillery fire and the warning time is about two or three seconds before impact.

‘If we turned on the air raid siren every time there was shelling the sirens would be non-stop.

A car with a whining transmission limps into the car park and the doctors shift nervously at the sound, which is vaguely like an approaching jet. ‘Yes, we feel fear,’ admits Dr Tumanov. ‘There is tremendous psychological stress living here.’

‘The shelling is indiscriminate,’ says his colleague. ‘There is no logic to the targeting. It is simply meant to cause fear.’

It also kills, of course. They relate a sad story about a couple who arrived in Nikopol from the Donbas region a month ago, having been driven from their home by the fighting in the east.

They rented a small apartment on the third floor of a block and on their first night settled down to sleep on a sofa bed. Shortly afterwards, a Russian shell blasted through the wall of their new home and they were killed instantly.

‘They were only in Nikopol one day and the war reached them here,’ says Dr Tumanov.

Did he think the UN inspectors’ visit will save Nikopol and beyond from a catastrophe?

He bursts into peals of laughter at my ‘naive’ question. ‘If there is a serious accident at the nuclear power plant, it will affect not only Ukraine but many of those countries which were at one point behind the Iron Curtain,’ he says.

‘They are the only ones, it seems, who truly know what we are dealing with here. Russia is like a rabid dog. You cannot apply logic to such creatures.

‘The countries in the West are still under a delusion that somehow they can deal with Russia amicably when, in fact, it understands only the language of force.

‘What is needed with such a dog is to build a very high fence and only then can we live side by side.’

Alas for battered Nikopol and Europe beyond her, even a high fence will not save it if the worst happens among those ominous shapes on the southern skyline.

Source: Read Full Article

-

Model, 32, who shot dead her British millionaire ex is freed

-

Russian officer describes moment ‘crazy colonel’ tortured Ukrainians

-

UK rail strike: Train drivers earn double that of teachers and nurses

-

Denver weather: Sunny warm day, possible rain in afternoon and night

-

ITV bosses at loggerheads with BBC after they 'poach' presenters