Of all the variables in our economy that I hate to predict, forecasting future movements in house prices would be at the top of my list.

That’s because the price of a home is, as I have observed over time, one of the prices in our economy that’s least determined by pure market forces and most determined by policy design.

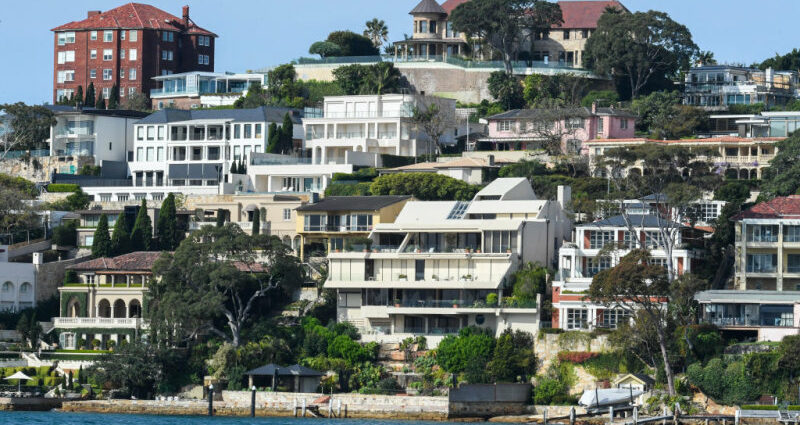

A booming housing market helped fuel an increase in the average Australian’s wealth in 2020.Credit:Peter Rae

From federal politicians, to central bankers, to prudential regulators, right down to state and local governments – there are just so many fingers in the pie. And while you might think they’re always working to make homes more affordable, history, sadly, suggests otherwise.

Politicians cry about housing affordability. But, when push comes to shove – and prices are actually falling – they consistently step in to inflate demand with boosted first home buyer grants and other measures. Will they do so this time? It’s hard to say.

On the supply side, the supply of new homes is heavily influenced by the zoning, regulation and taxation decisions of governments.

On the demand side, population growth and wages growth are less obviously driven by government decisions, but by far the biggest factor influencing the demand for housing – how much people have to spend – is the cost of borrowing, which is set almost entirely by the Reserve Bank.

From highs of 17 per cent or so during the early 1990s, the slow grind south in the official cash rate – to a low of almost zero during COVID – has undoubtedly been the major driver of turbocharged average home price growth during the last few decades.

It’s hard to see that tailwind for prices continuing, however, now that official rates have hit the effective ‘zero lower bound’ of policymaking, ie zero per cent – albeit bounced up since then.

The Reserve’s inclination will be to talk tough, but err on the side of caution in raising rates much further now.

As a general rule of thumb, I reckon you can take the high point of your property’s valuation during COVID – when rates were at almost zero per cent – and assume that will represent something of a high watermark for a while to come.

In the short to medium term, of course, prices are receding from those levels, and will fall further.

Why? Because when you make it more expensive to borrow, people can’t borrow as much from a given income and less borrowed means less spent at auctions.

That’s pretty obvious. But another less obvious factor dampening borrowing capacity and home prices currently is the impact general inflation on people’s borrowing capacity.

When you go for a loan, your surplus cash flow is calculated as your income minus non-housing living expenses. The default assumption for living expenses – the so-called ‘Household Expenditure Measure’ – gets automatically indexed higher each quarter with inflation.

So, if your annual after-tax income is $100,000, and non-housing living expenses were $60,000, you’d have $40,000 surplus cash flow to afford your new mortgage.

But inflate those living expenses by the full latest inflation figure of 7.3 per cent, and that brings them to $64,380, leaving you only $35,620 surplus cash flow to service your loan – assuming no change to your income.

So, as you can see, even absent any interest rate hikes, borrowers have suffered a significant reduction in their ability to service loans thanks to the rising cost of living.

Add rate hikes, of course, and borrowing capacity has shrunk dramatically.

Those who fixed their mortgage rates last year will be more than $20,000 better off than those on a variable rate over the next two years, data shows.Credit:Peter Rae

According to AMP chief economists Shane Oliver, rate hikes since last April have reduced the home buying power of an average full-time earner with a 20 per cent deposit by 27 per cent, from $600,000 to $440,000.

Viewed in that light, the 8 per cent fall in home values so far since their highs early last year looks relatively modest. Oliver predicts further price falls of about 9 per cent out to about September.

Much depends, of course, on where the Reserve Bank takes the cash rate from here.

Money markets are still betting the cash rate will hit 4 per cent, from 3.1 per cent currently. If that happens, Oliver predicts an even sharper total decline in prices of 30 per cent total.

Only time will tell, of course. I suspect the Reserve’s inclination will be to talk tough, but err on the side of caution in raising rates much further now, as opposed to jacking rates up only to have to cut them by years end. A major ‘x-factor’ remains how households on ultra-low, sub-2 per cent fixed rates respond as the bulk roll off onto rates closer to 6 per cent throughout this year.

Given the myriad forces in play, it’s hard to give firm predictions. A final force is that our prudential regulator has, at the urging of lenders, also shown a tendency to rush in to support home values with relaxed lending standards.

I suspect if rates rise much further from here, there will soon be great pressure applied to have the current 3 percentage point stress test applied to new borrowers relaxed (that’s the test to see if borrowers can afford their mortgage if interest rates were 3 percentage points higher than the current loan rate).

Some lenders are already pushing longer repayment terms, 40-year loans are available from some, which has the effect of reducing monthly minimum repayments and therefore boost total borrowing power.

So, do strap yourself in for more home price falls ahead. But don’t be surprised if outcomes depart from predictions. When it comes to home values, it’s anyone’s guess.

The Business Briefing newsletter delivers major stories, exclusive coverage and expert opinion. Sign up to get it every weekday morning.

Most Viewed in Business

From our partners

Source: Read Full Article

-

Beware unregulated ‘quick fix’ pay advances

-

Why it’s time to redefine how we think about retirement

-

Olympus Profit Jumps On Strong Revenues; Ups Annual Guidance

-

Hands off our super! There are better ways to make housing affordable

-

Kingspan H1 Profit Climbs, Margin Down; Lifts Dividend; Retains Outlook – Quick Facts