In May, Micron Technologies, the Idaho chipmaker, suffered a serious blow as part of the U.S.-China technology war. The Chinese government barred companies that handle crucial information from buying Micron’s chips, saying the company had failed a cybersecurity review.

Micron said the change could destroy roughly an eighth of its global revenue. Yet in June, the chipmaker announced that it would increase its investments in China — adding $600 million to expand a chip packaging facility in the Chinese city of Xian.

“This investment project demonstrates Micron’s unwavering commitment to its China business and team,” an announcement posted on the company’s Chinese social media account said.

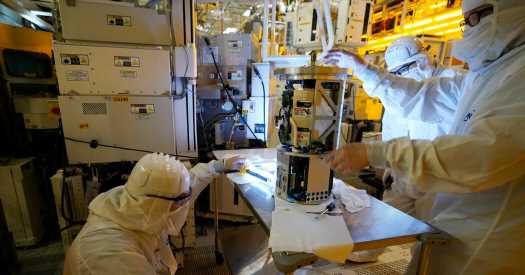

Global semiconductor companies are finding themselves in an extremely tricky position as they try to straddle a growing rift between the United States and China. The semiconductor industry has become ground zero for the technology rivalry between Washington and Beijing, with new restrictions and punitive measures imposed by both sides.

U.S. officials say American products have fed into Chinese military and surveillance programs that run counter to the national security interest of the United States. They have imposed increasingly tough restrictions on the kind of chips and chip-making equipment that can be sent to China, and are offering new incentives, including grants and tax credits, for chipmakers who choose to build new operations in the United States.

But factories can take years to construct, and corporate ties between the countries remain strong. China is a major market for chips, since it is home to many factories that make chip-rich products, including smartphones, dishwashers, cars and computers, that are both exported around the world and purchased by consumers in China.

Overall, China accounts for roughly a third of global semiconductor sales. But for some chipmakers, the country accounts for 60 percent or 70 percent of their revenue. Even when chips are manufactured in the United States, they are often sent to China for assembly and testing.

“We can’t just flip a switch and say all of sudden you have to take everything out of China,” said Emily S. Weinstein, a research fellow at Georgetown’s Center for Security and Emerging Technology.

The industry’s reliance on China highlights how a close — but extremely contentious — economic relationship between Washington and Beijing is posing challenges for both sides.

Those tensions were reflected during Treasury Secretary Janet L. Yellen’s visit to Beijing this week, where she tried to walk a fine line by faulting some of China’s practices while insisting the United States was not looking to sever ties with the country.

Ms. Yellen criticized punitive measures China has recently taken against foreign firms, including limiting the export of some minerals used in chip making, and suggested that such actions were why the Biden administration was trying to make U.S. manufacturers less reliant on China. But she also affirmed the U.S.-China relationship as strategic and important.

“I have made clear that the United States does not seek a wholesale separation of our economies,” Ms. Yellen said during a roundtable with U.S. companies operating in China. “We seek to diversify, not to decouple. A decoupling of the world’s two largest economies would be destabilizing for the global economy, and it would be virtually impossible to undertake.”

The Biden administration is poised to begin investing heavily in American semiconductor manufacturing to lure factories out of China. Later this year, the Commerce Department is expected to begin handing out funds to help companies build U.S. chip facilities. That money will come with strings: Firms that take funding must refrain from expanding high-tech manufacturing facilities in China.

The administration is also weighing further curbs on the chips that can be sent to China, as part of a push to expand and finalize sweeping restrictions it issued last October.

These measures could include potential limits on sales to China of advanced chips used for artificial intelligence, new restrictions for Chinese companies’ access to U.S. cloud computing services, and restrictions on U.S. venture capital investments in the Chinese chip sector, according to people familiar with the plans.

The administration has also been considering halting the licenses it has extended to some U.S. chipmakers that have allowed them to continue selling products to Huawei, the Chinese telecom firm.

Japan and the Netherlands, which are home to companies that make advanced chip manufacturing equipment, have also put new restrictions on their sales to China, in part because of urging from the United States.

China has issued restrictions of its own, including new export controls on minerals used in chip manufacturing.

Amid tighter regulations and new incentive programs from the United States and Europe, global chip companies are increasingly looking outside China as they choose the locations for their next major investments. But these facilities will likely take years to construct, meaning any changes to the global semiconductor market will unfold gradually.

John Neuffer, the president of the Semiconductor Industry Association, which represents the chip industry, said in a statement that the ongoing escalation of controls posed a significant risk to the global competitiveness of the U.S. industry.

“China is the world’s largest market for semiconductors, and our companies simply need to do business there to continue to grow, innovate and stay ahead of global competitors,” he said. “We urge solutions that protect national security, avoid inadvertent and lasting damage to the chip industry, and avert future escalations.”

Ana Swanson is based in the Washington bureau and covers trade and international economics for The Times. She previously worked at The Washington Post, where she wrote about trade, the Federal Reserve and the economy. More about Ana Swanson

Source: Read Full Article

-

Gabriel Byrne’s Broadway Solo Show ‘Walking with Ghosts’ To Close Early After Box Office Struggle

-

India’s plan to produce ethanol from 2G sources delayed

-

SAG-AFTRA President Fran Drescher Back To Lead Last-Ditch Effort To Reach A Contract – After A Weekend In Italy Mugging For Cameras With Pal Kim Kardashian At Dolce & Gabbana Show

-

Judge Delays Decision on Hong Kong’s Request to Ban Protest Song Online

-

U.S. Stocks May Give Back Ground On Jobs Data, Disappointing Tech Earnings